Ancient Greeks called it phthisis. Ancient Romans, tabes. In Hebrew, it is Schachepheth. 1700s Europe, The white plague. Consumption. Officially, it’s tuberculosis, an ancient, deadly scourge with many names. Tuberculosis makes its victims feel weak, nauseous, suffer fevers, night sweats, deep-chest coughing, and even cough up blood. Untreated, it can kill half of its victims within five years. Things took a turn when Dr. Robert Koch identified the tuberculosis bacterium in 1882. There was no mystery any more about what caused tuberculosis, but its deadly reign continued. In 1915, it was the leading cause of death in the U.S.A. To battle the microbial monster, doctors isolated children in preventorium to give them to sunshine, fresh air, and good nutrition. Patients, nicknamed “Chidren of the Sun,” lived a restful life of outdoor play. But these children had to leave home at a young, vulnerable age, a scary prospect for a child.

Tuberculosis: An Ancient Scourge & A Modern Problem

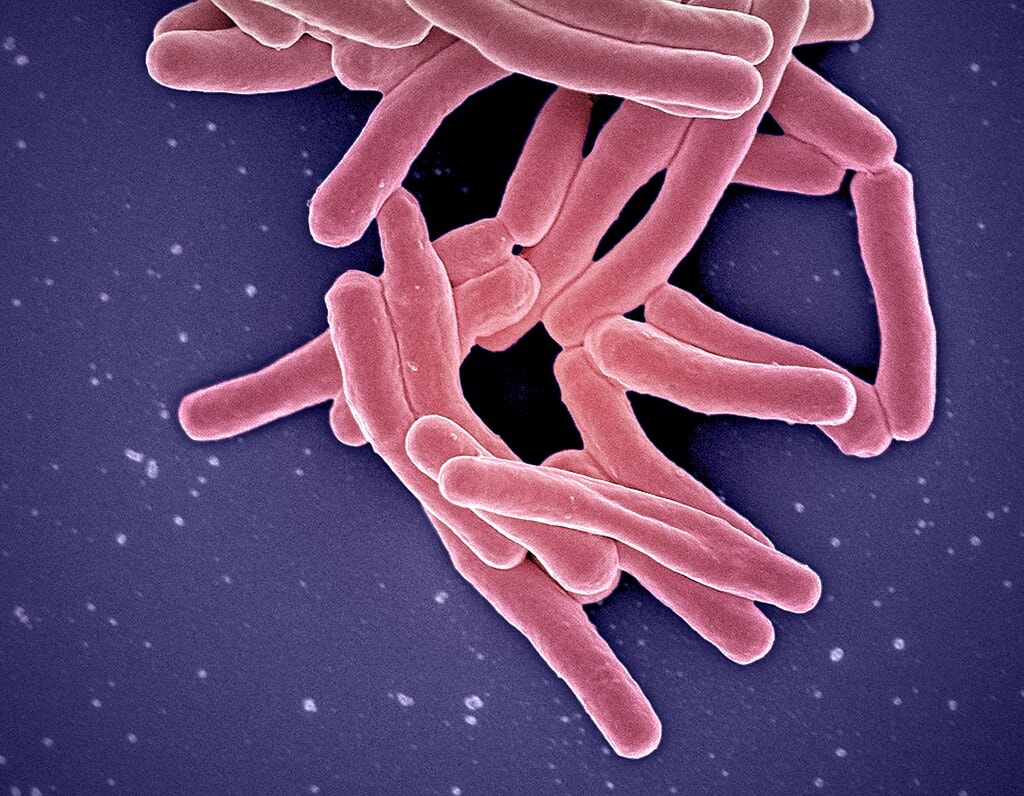

Historians and scientists have a theory that Mycobacterium tuberculosis (the tuberculosis bacteria) has been around as long as 150 million years. The earliest evidence of tuberculosis is found in the now-underwater Atlit Yam, a Mediterranean city off the Israeli coast. Archaeologists found markers of the disease in remains found in the city. Tuberculosis (or what historian believe is tuberculosis) is found in written records dating back 3,300 to 2,300 years in India and China. European records indicate tuberculosis killed up to twenty-five percent of the population between 1600 CE and 1800 CE. Formal data about cases and death rates were recorded started in 1889, when the New York City Department of Health and Hygiene required doctors report cases of tuberculosis to the health department. At that time, governments and public health departments started to get involved in tuberculosis treatment and prevention.

Tuberculosis Stages

Tuberculosis is a bacterial illness, spread by particulates when an infected person coughs, sneezes, speaks, breathes, or otherwise expels the bacteria from their lungs, or consumes infected food or drink (particularly milk). But not everyone exposed to tuberculosis gets sick. A person can test positive for tuberculosis but never show any symptoms, nor do they spread the disease (latent tuberculosis infection). Their immune system fights the bacteria. It cannot grow or become dangerously infectious. But if the bacteria multiply to the point where the person’s immune system cannot fight it anymore, they are diagnosed with tuberculosis disease. This has historically been dangerous and deadly. Tuberculosis disease is rather sly; while many people stay in the latent stage of infection, others develop symptoms within weeks, and others won’t get sick for years later. Governments and health officials in the early 1900s experimented with methods to stop the spread of tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis Sanitoriums

Sanitoriums isolated people with full-blown tuberculosis disease from the general population in an effort to reduce the spread. A child with tuberculosis risked spreading the disease to family members, friends, schoolmates, anyone they came into contact with. Sending a child with tuberculosis to the sanitorium, as terrifying as this would be for them, would remove them from these external contacts and decrease the risk of spreading the disease to others. But the child had to experience diagnosed, symptomatic tuberculosis before admission to a sanatorium. The sanitorium would treat the child, trying to help them recover from the disease (or, in terrible cases, not recover and be chronically ill or die). A preventorium is a whole different side of tuberculosis treatment. Preventoriums intended to stop the tuberculosis exposure or latent tuberculosis from moving into the tuberculosis disease stage, arresting it before a person even got sick.

Classifying the Infected

In 1908, Clemens von Pirquet identified a way to classify patients. Prior to his work, there were two classifications of people, “sick” and “well.” But Pirquet’s findings created a third group, the infected but without active disease, or pre-tubercular. The disease could linger, latent, for years before the patient showed symptoms. The infection could linger dormant for years and evolve into the active disease phase when they were adults. Children and their parents could not know when or how the disease would present itself. The children had a time bomb hiding inside their bodies. Government and public health officials focused their efforts on these people, particularly children, as they had the lowest incidence of active disease. Officials hoped that an early intervention might prevent these children from moving into the disease phase.

The Preventorium as a Public Health Response

Pirquet’s test to determine if someone were sick, well, or pre-tubercular meant children could be categorized and observed for the illness. As these children were tested and categorized, public health officials analyzed resulting data to see who fell into each category. Doctors and health officials were trying to find a genetic or environmental trend that would indicate whether tuberculosis would move from latent to fully formed disease. This analysis revealed wealthy children tended not to test positive for the tuberculosis indicator tuberculin. Some analysts took this to mean that children from poor conditions had “fewer genetic resources” to fight off tuberculosis. The officials, in an effort to slow the disease from spreading, experimented with removing children from their home and isolating them to help stave off the transformation of the disease.

France Paved the Preventorium Path

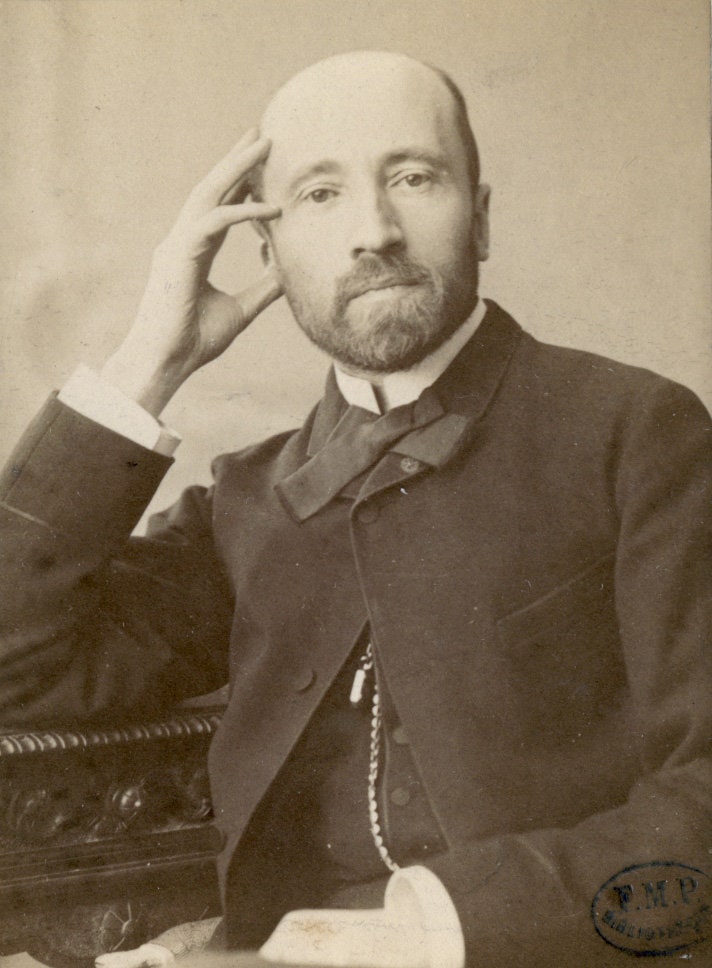

France had been on the forefront of child welfare by the late 1800s, regulating child labor and parental custody at the government level. In France, social welfare fell under governmental duty, but that sensibility didn’t always extend to public health. But tuberculosis data indicated a larger public interest in preventing the spread of tuberculosis. Government officials couldn’t agree on the details, though. The officials argued about mandating doctors to report cases of tuberculosis to health officials. They also argued about offering financial assistance to people infected with tuberculosis, and whether the government should be involved in planning for public health initiatives. Despite the debate, French doctor Jacques Joseph Grancher considered the tuberculosis statistics and found them alarming, and decided to take firm action. He opened a prevention program in 1903, to isolate and supervise low-income children exposed to the disease.

The Grancher System: Separation from Family

Dr. Grancher’s preventorium program wasn’t the separate preventorium this philosophy would become. Instead, the early preventorium program identified low-income families with children exposed to tuberculosis in their home. Children aged three to ten years were sent to families living in rural areas around France. This would, in theory, expose them to fresh air and sunshine, and the farm labor would do them some good. Nurses regularly visited the families to check on the child’s health and care. Their parents were allowed to visit for two days, four times a year. The children had to remain with these families for the remainder of the year and could not go back to their homes during this time. Because tuberculosis could lie dormant for years, the children often stayed with these families until they reached age thirteen. These former patients could return home – if the foster family hadn’t adopted them already.

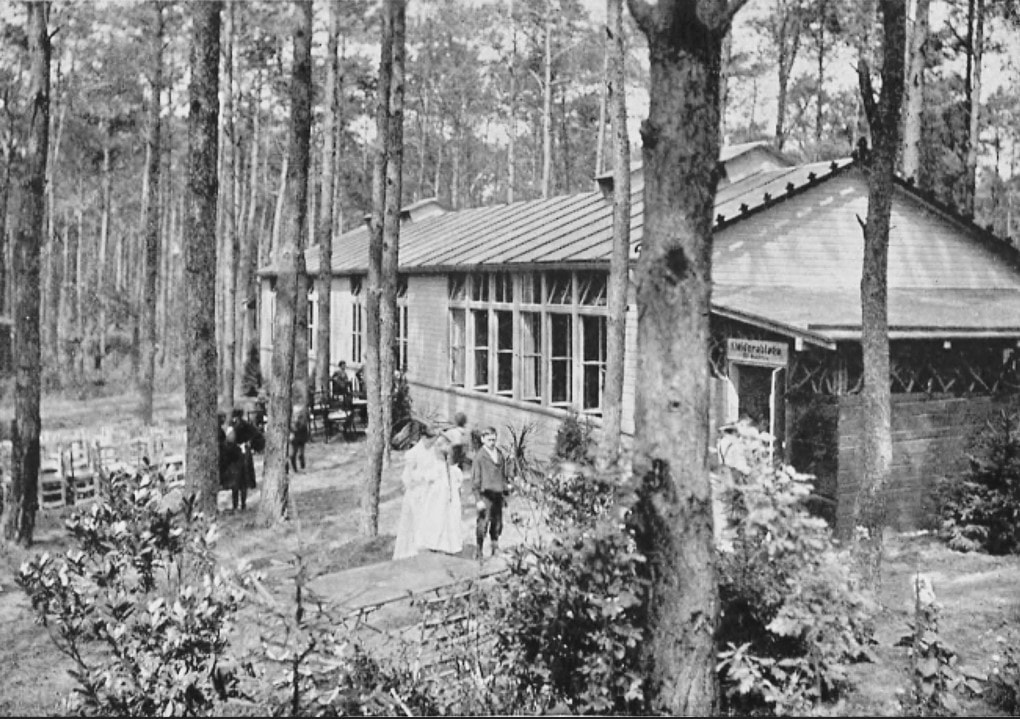

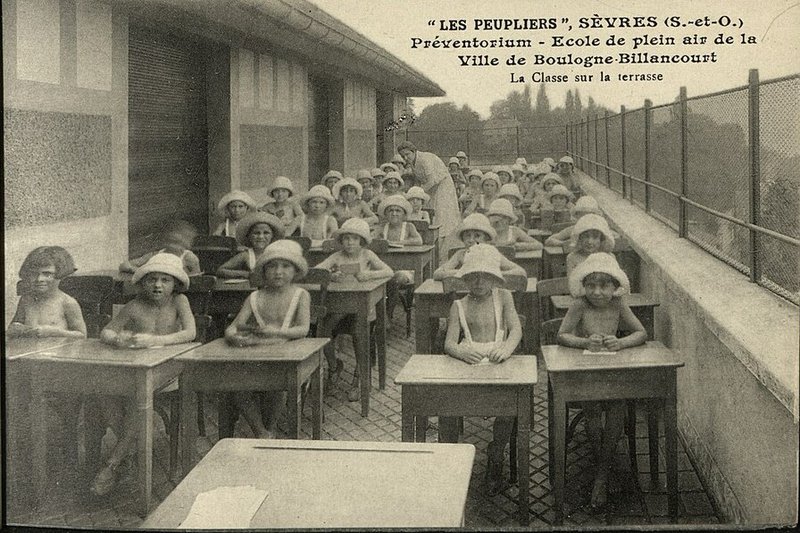

Waldschule and the German Open-Air Schools

While France “boarded out” children to rural families, German pre-tubercular children attended open air schools (waldschule). Charlottenburg Waldschule, about half an hour away from Berlin, opened in 1904 as a way to enhance the children’s resistance to tuberculosis through fresh air, nutrition, and rest. The year-round school settled in an isolated wooded area on the edge of town. This kept the children away from large populations where they could unknowingly spread the disease. Contrary to the French system, the German waldschule allowed its students to return home for the evening. They spent eleven hours a day at school, ate five meals, and did three hours of schoolwork. To build up their strength, they would bathe and have mineral oil scrubs, and were forbidden from excessively vigorous play. Charlottenburg reported an improvement in 70% of its patients. This reported success rate sparked a wave of similar open-air schools opening around Germany.

Preventorium: A Campus for the Healthy

Grancher’s system and the German waldschule evolved from fostering children into large-scale, specific use facilities much like sanitorium. The sanitorium, a full-service boarding facility, focused on treatment and recovery. Preventorium,also a full-service facility, focused their efforts on stopping the disease before it became a full-blown case of deadly tuberculosis. Preventorium housed healthy children, who were declared ‘pre-tubercular.’ They had the potential ofdeveloping the disease. The National Tuberculosis Association’s Committee on Preventoria defined the institutes as “…a 24-hour institution for the care and observation of children substandard in health.” The definition didn’t specify any one disease, but later criteria developed by the Committee limited their patients to pre-tubercular children. Dr. H. E. Kleinschmidt, writing in 1930, makes it clear that “…a sick child should not be in a preventorium, which is in fact a school.”

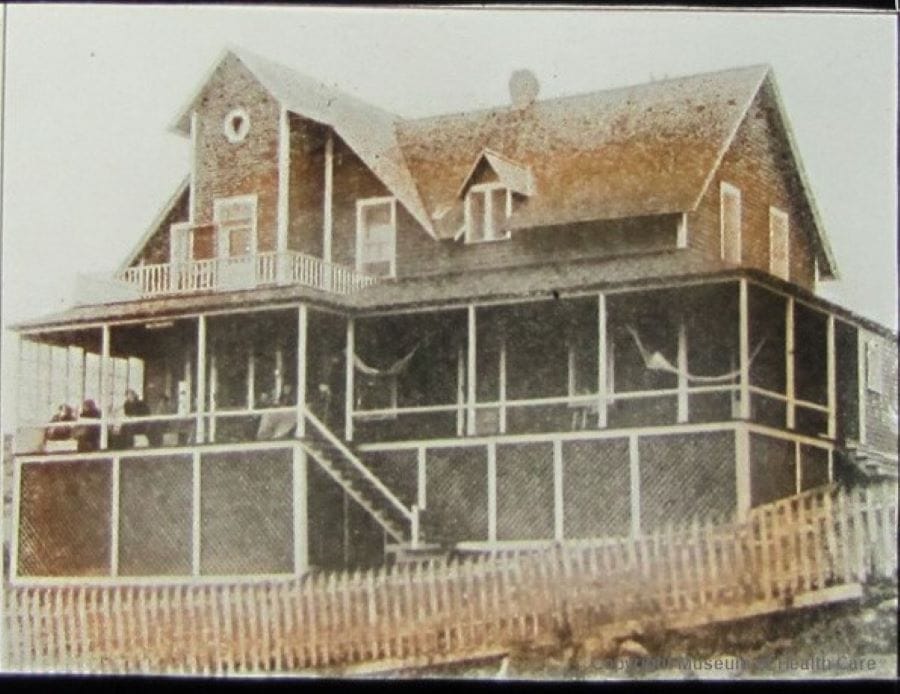

Brehmer’s Rest

Canadian convalescent home Saint Agathe des Monts, also known as Brehmer’s Rest, opened in 1906. This facility for adults recovering from severe illness isolated patients from the general population as they built up their strength and immunity . Facility directors particularly focused on building patients strength to fight off tuberculosis, which reared its ugly head periodically as a highway to respiratory failure. Over time, doctors observing the success of Brehmer’s Rest saw value in separating potentially tubercular people from the rest of the population to avoid spreading infection. Facilities were established across North America based on the Brehmer’s Rest ‘isolate and treat’ model had one goal: to stop the tuberculosis-exposed patent from developing a full-blown case of tuberculosis and prevent further illness and spread of the disease.

The North American Crisis

The French ‘boarding-out’ program, the German waldschule, and Brehmer’s Rest provided the model for pediatrician and tuberculosis prevention specialist Dr. Alfred Hess’s efforts to slow the spread of tuberculosis in the United States. The influx of immigrants coming to the United States through Ellis Island made tuberculosis prevention especially critical. While tuberculosis cases declined in middle- and upper-income families, low-income populations still had an alarming rate of infection. The New York City’s health department presented data showing local tenements housed about 40,000 children exposed to tuberculosis infected by a tubercular adult. In 1909, he established a preventorium in Farmingdale, New Jersey, to build the children’s ability to keep the disease at bay. Children at the preventorium would improve their chances of fighting off the disease by isolating them and providing a therapeutic experience away from infected people in their home environment.

Preventorium in North America

Farmingdale accepted children from four years old to fourteen. Their patients came from crowded urban areas and had at least one parent with tuberculosis disease. These children appeared pale, malnourished, or generally unhealthy. Patients at Farmingdale boarded at the facility, undergoing its strict health regimen. The preventorium was a healthy-living boarding school, where children were to rest, attend school, eat nourishing meals, and spend time in the open air and sunshine. Officials built the facilityin a remote area with lots of forest and a lake or river for swimming on warm days. This would be a model for future facilities. The average stay lasted three to six months, but given the uncertain span between exposure and full-blown disease, many students stayed much longer than that. Years, even. In the Minnesota preventorium system, patients reportedly stayed for an average 2.5 years, some as long as four to even nine years.

Preventorium Patients

Defining candidates for the preventorium wasn’t standardized among the facilities. Some preventoriums might accept children actually diagnosed with tuberculosis but whose symptoms were extremely mild. Others might accept children diagnosed but asymptomatic. Preventorium might accept children who were exposed to tuberculosis at home or at school but hadn’t been diagnosed with the disease. Other facilities accepted non-exposed patients from low-income families. These children were merely malnourished. Officials believed this made these children more susceptible to tuberculosis. Some patients weren’t even there for tuberculosis. Children with heart disease or other ‘acceptable’ health conditions were also admitted to preventorium. The acceptance process was very subjective, based on the decision of the facility’s managers.

Standardizing Preventorium Patient Criteria

Preventorium were free services, and patients were voluntarily admitted (at least their parents voluntarily admitted them), but some needed a physician’s reference. In 1927, the Committee on Preventoria of the National Tuberculosis Association set some standards for the acceptance of patients. They defined six official criteria:

- Children exposed at home or had an immediate family member die of tuberculosis.

- Children who had tuberculosis, but recovered, with no lesions, and didn’t need any more care or observation.

- Malnourished children.

- Children who “tire easily and who are unable to carry on their class work.” This definition did not specify whether this had to be disease-related or if it covered children who were merely not interested in school.

- Children who missed a lot of school due to colds, bronchitis, or other respiratory illnesses.

- Children who had certain types of rheumatic heart disease.

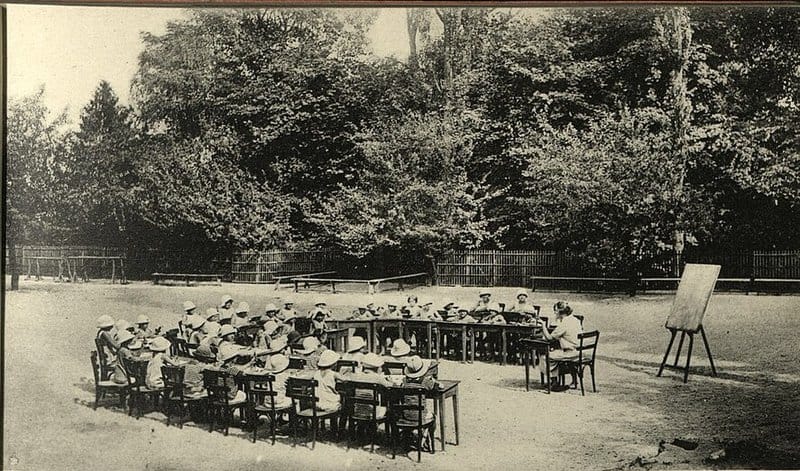

Preventorium Had No Universal Standard of Care

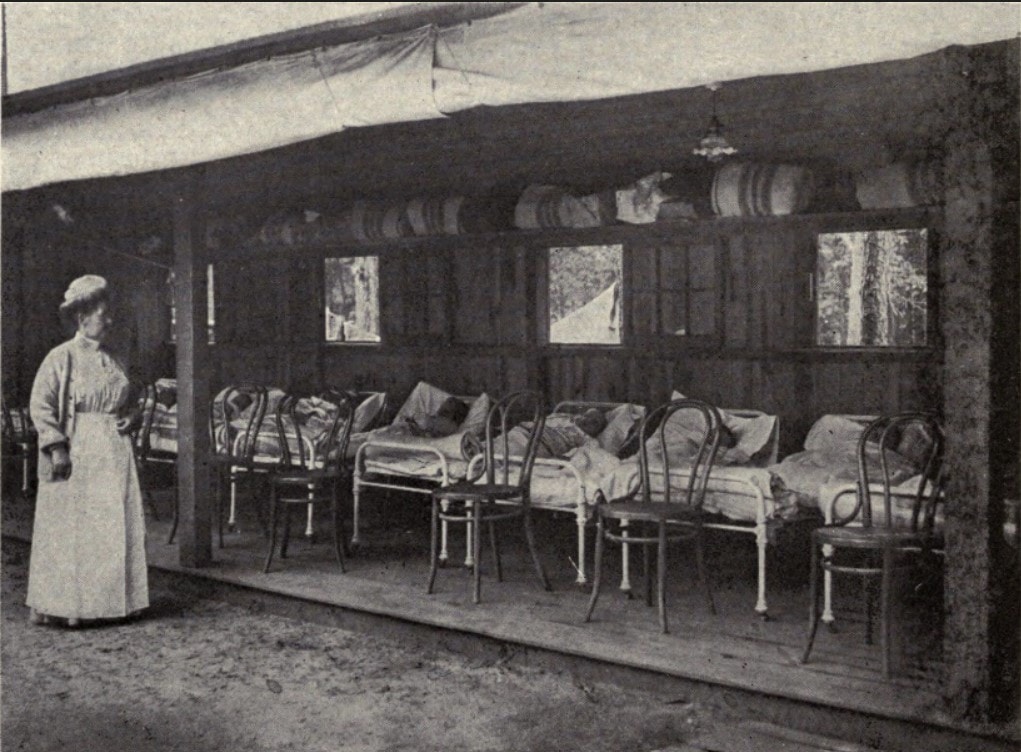

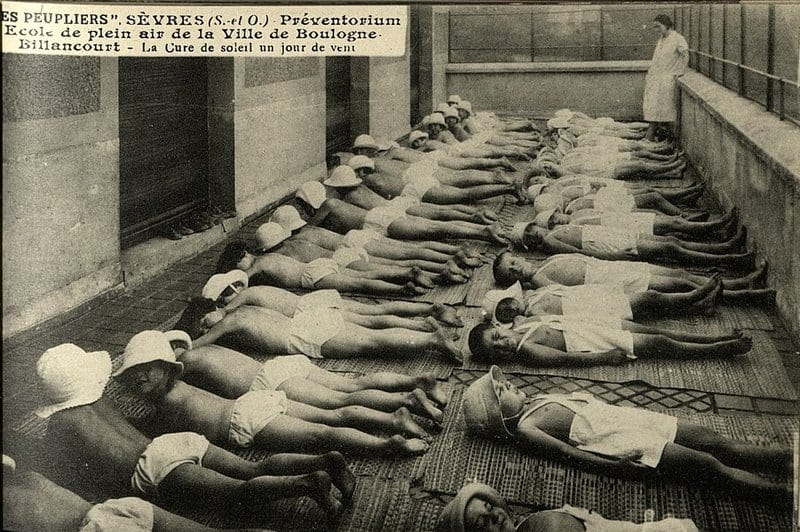

While preventorium grew in popularity, there wasn’t any standardized ‘best practices’ to guide the operation and treatment of their patients. Each facility chose its own methods of operation and treatment. But patients at any facility, like Farmingdale preventorium in the United States or the Hauts-de-Seine in France, could expect a lot of outdoor time; to the point where some children had their school lessons outside and desks set up in the fresh air and sunshine. Children took their many hours of rest in beds or cots laid out on porches or with the dormitory windows wide open. Patients and their families expected the preventorium to provide good nutrition, but what that meant and what they served was up to the facility and its cooks. There was no single oversight to preventorium, each facility decided for itself how it met the needs of its patients.

Preventorium Residence

Unlike the French boarding-out method, where patients would get four visits per year from their families. These children had to stay at their new homes for years at a time, until they turned thirteen. Preventorium facilities took a more family-friendly approach to the children’s confinement. Preventorium like the Lucas County, Ohio, facility served as a boarding school. Patients would board at the schools during the week but went home for the weekend. The Lymanhurst School in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA wasn’t even a boarding facility. Patients attended the preventorium during their school days and went home in the evenings. These facilities resembled traditional schools more than sanitoriums, but with a nurse or doctor on hand all the time to monitor the children’s health and record their physical condition.

Preventorium ‘Uniforms’

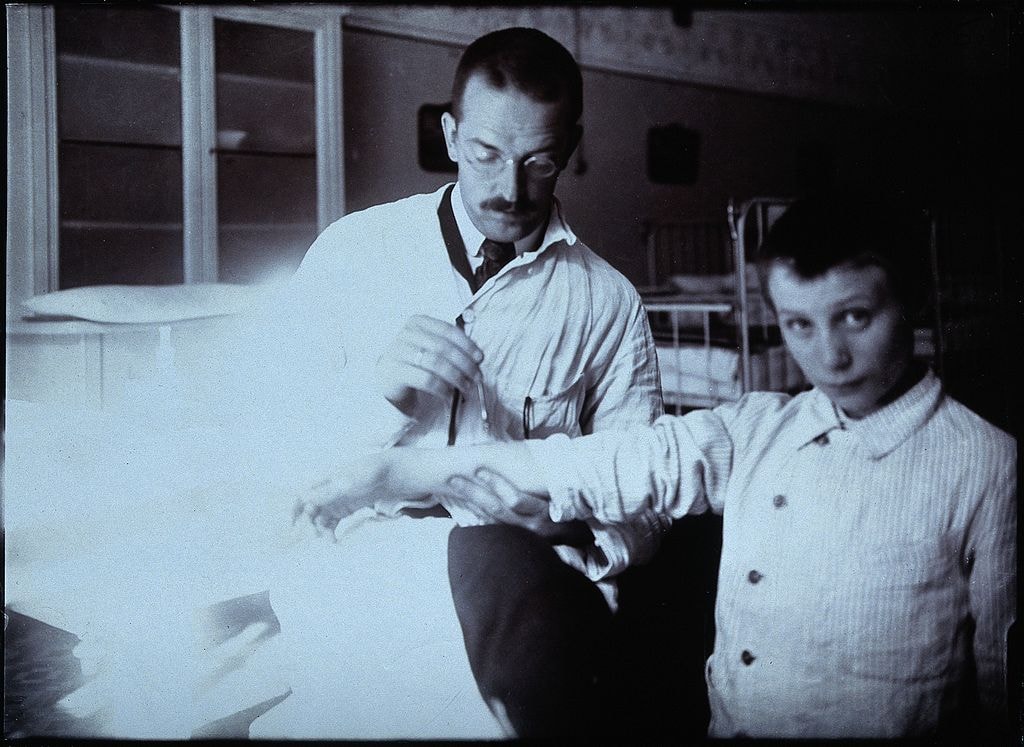

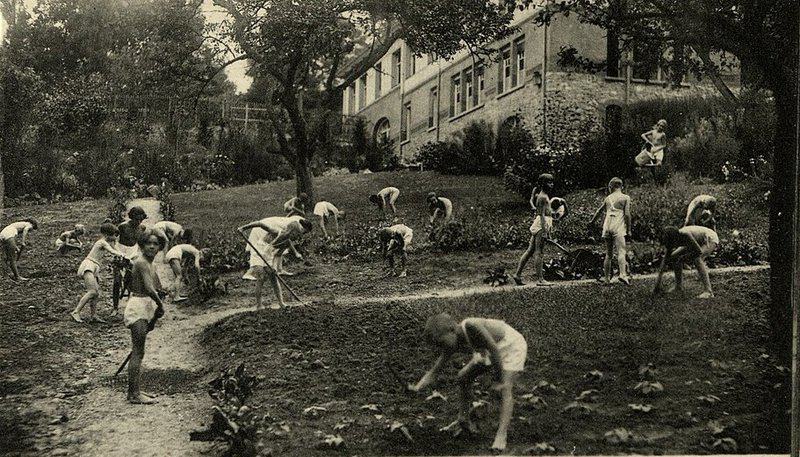

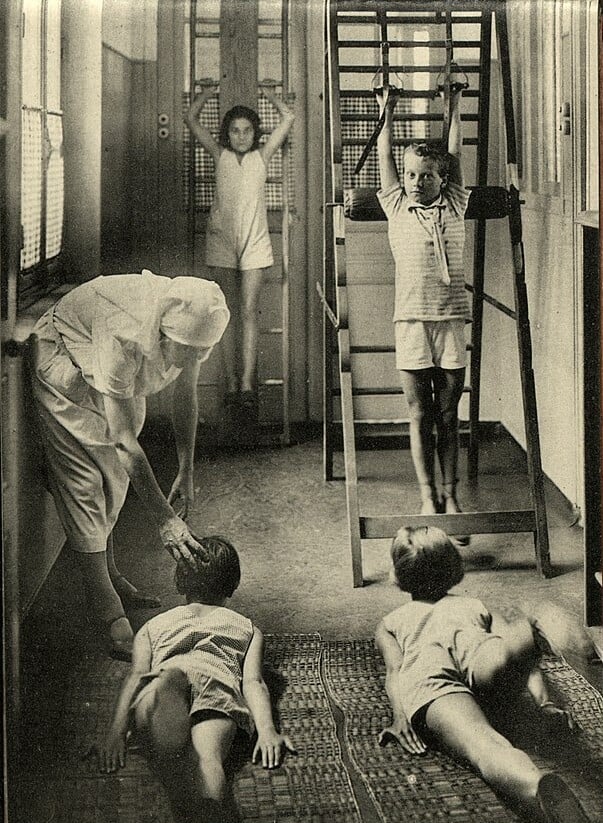

Preventorium had a rigid school uniform. Perhaps patient garb is better described as an anti-uniform. Preventoriums were determined to have students get as much fresh air and sunshine as humanly possible to increase their tuberculosis resistance. This means getting sunshine everywhere. Boys at many preventorium wore a garment called a drape during the warm months and indoors, as seen in this photo. Drapes were nothing more than a loose-fitting loincloth that covered their genitals and buttocks, but as little and as loosely as modesty allowed. Girls wore a one-piece garment that exposed most of their legs and arms. The patients donned ‘uniforms’ of light, white fabrics that fit loosely to allow maximum light and air exposure.

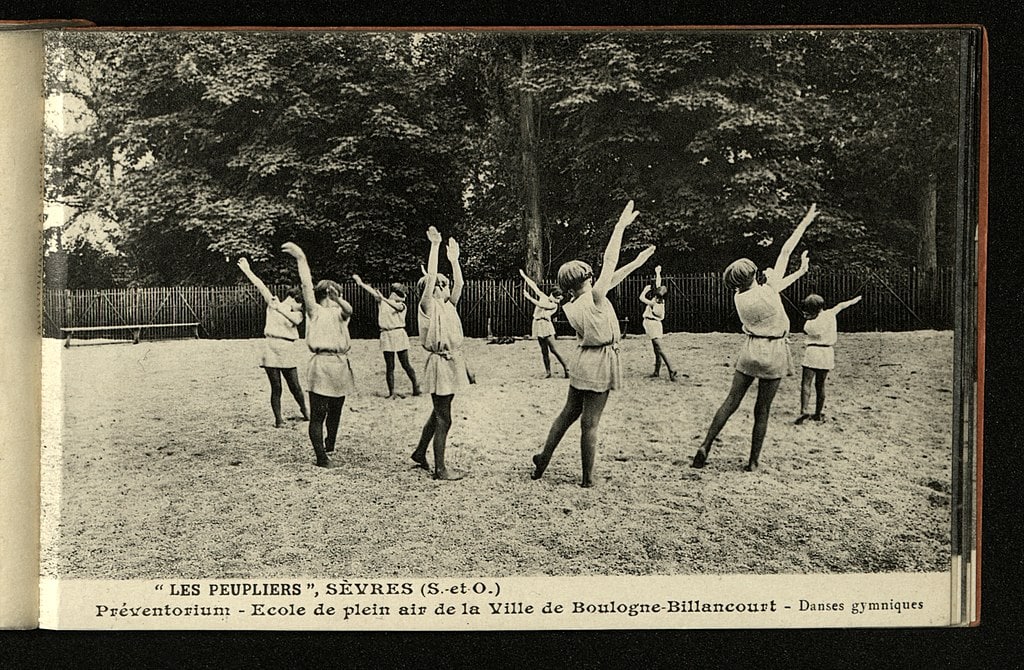

Exercise and Play

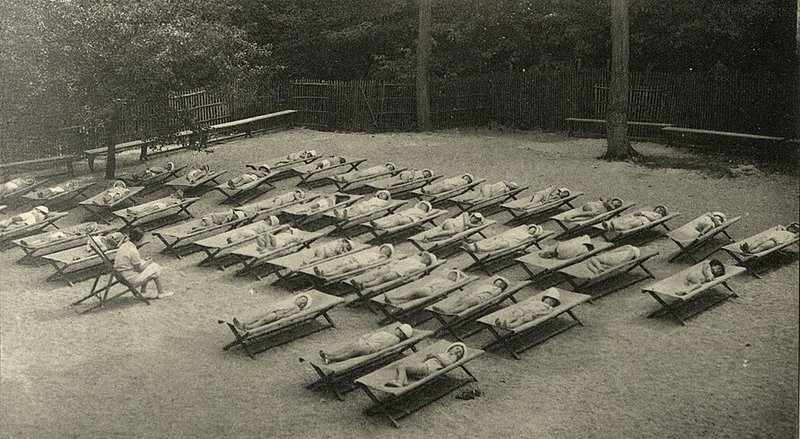

Despite the pains of being away from home and the possibility of the latent tuberculosis evolving into the deadly disease, things weren’t all bad in preventoriums. One “treatment” requried the child be “relieved of all possible strain, which means the avoidance of strenuous exercise and burdensome schoolwork.” The goal was to build up the child’s health with food, fresh air and reduce the everyday stresses that might trigger latent tuberculosis to evolve into tuberculosis disease. In addition to preventing overexertion, Preventorium, like their sanitorium counterparts, used heliotherapy. Heliotherapy exposed children to as much sunlight as possible to restore health and vigor. To that end, unlike the actually ill children, preventorium children were expected to engage in light, nonstrenuous play outdoors, weather permitting. Heliotherapy gave preventorium patients their nickname, “Children of the Sun.”

Nutrition

Dr. Everett Greer of the Ramsey County Preventorium in Minnesota recorded in 1926, “Practically all these children come to us below weight…hence…food of the right kind is an imperative need and one which is fulfilled without stint.” A menu from the Fort Alexander preventorium, caring for indigenous Canadian patient populations, offers insight into the nutritional plan for the children. The children had a staple of fruit, vegetables, and milk with every meal. Breakfast added bran meal, Cream of Wheat, or oatmeal. Lunch varied a bit, with proteins like liver, bacon, roast beef, or stew and potatoes, crackers, beets, or rice pudding for starch. Dinner was light, with macaroni, eggs, sandwiches, and salads along with the staple menu. And much to the children’s disgust, they swallowed a dose of cod liver oil each day. Preventorium would additionally offer nutrition classes to make sure patients developed lifelong good eating habits.

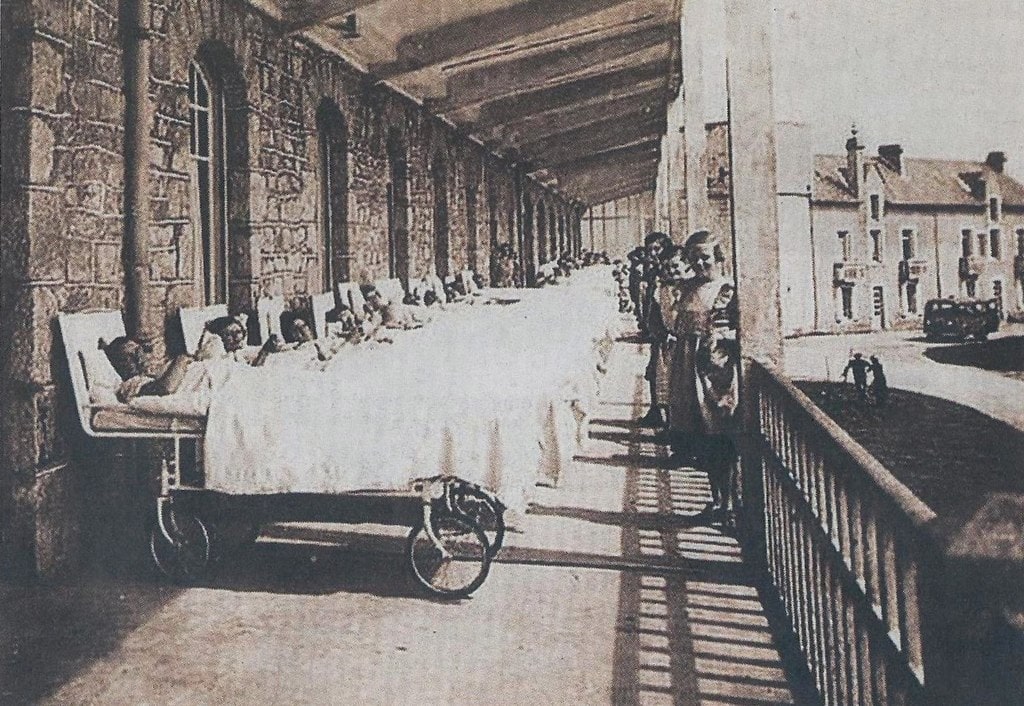

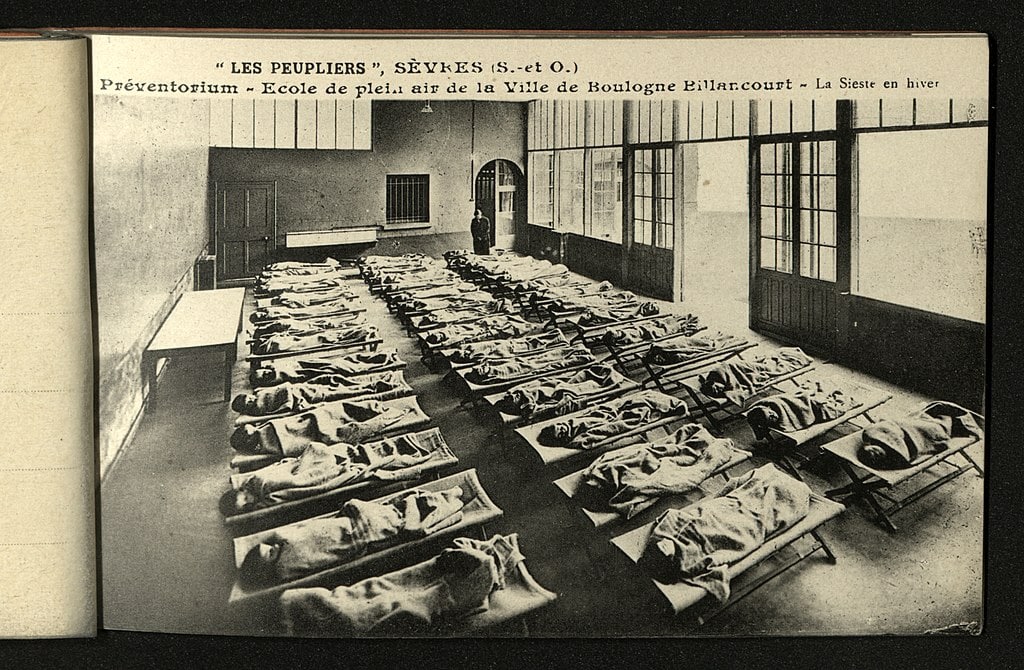

Rest

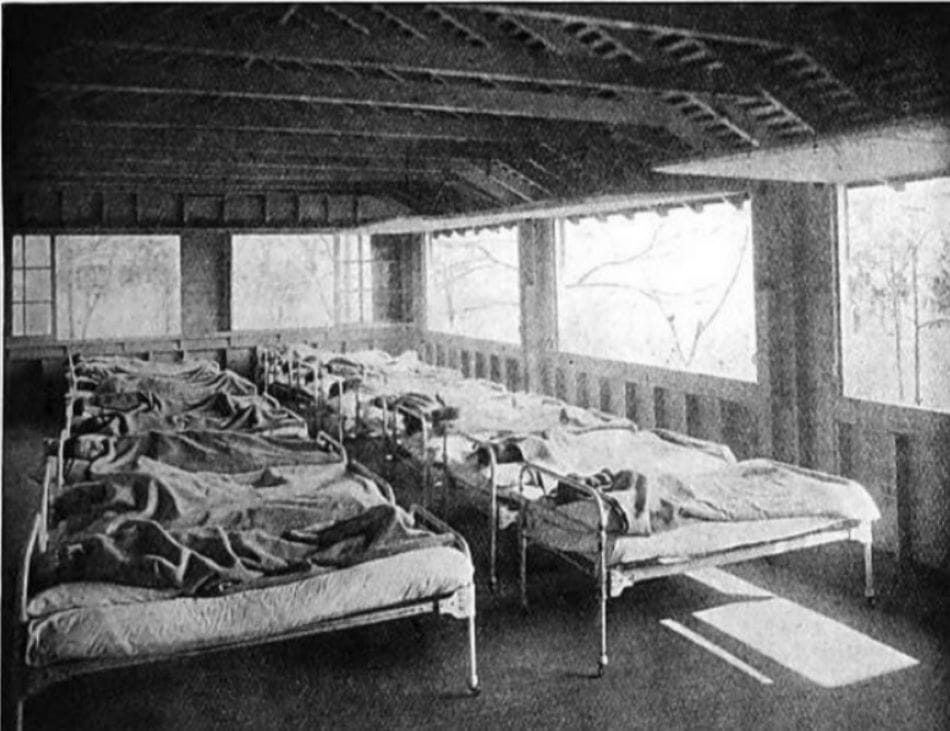

Even modern medical professionals agrees that a lack of sleep or interrupted sleep patterns are bad for tuberculosis patients. Preventorium addressed this problem by ensuring patients had plenty of sleep and rest during their daily activities. Patients of preventoriums would, through most of the spring, summer, and fall, sleep on dedicated outdoor porches. Their sleep period ensured maximum rest by design. They scheduled twelve hours for sleep at night. In addition to this abundant sleep at night, they also required a rest time during the day. They scheduled this between lunch and afternoon activities. Students at the Fort Alexander facility would wake at 7:00 AM, and start their day. They had a one-hour rest period at 12:30 pm and went to bed at 7:00 pm.

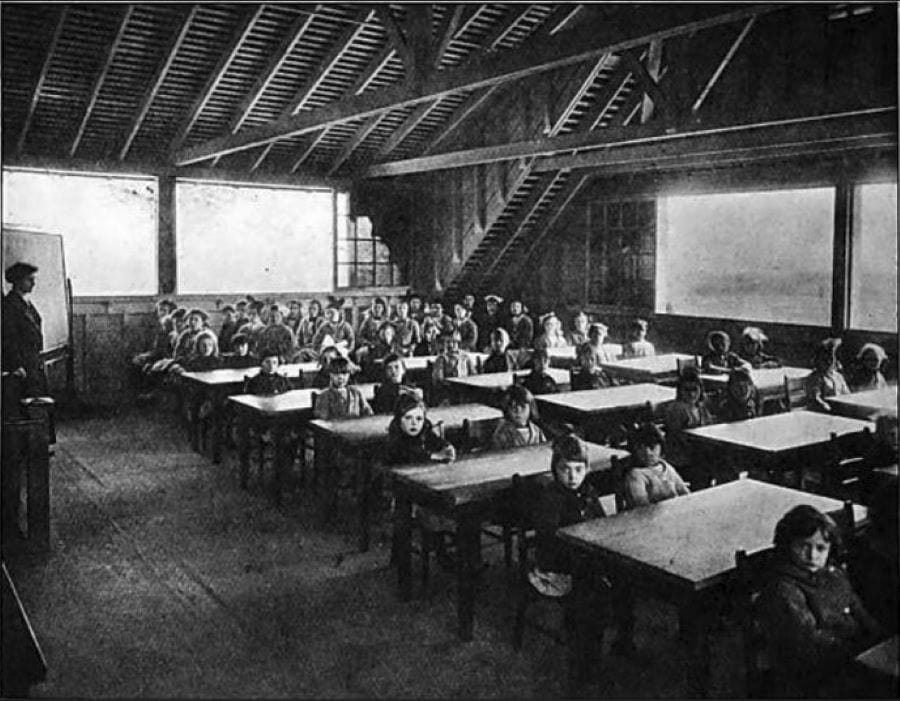

Education

Patients had to attend the preventorium school to keep up with their peers academically. They would, however, only do two, three, or four hours of classroom time to reduce their stress levels. The classrooms were as open as their rest area; some kept their large windows open to allow airflow, others moved the desks outside as weather allowed. In winter, students would wear their coats, boots, hats, and mittens or gloves during their school hours. When the winter weather was too harsh, the desks were indoors. But windows remained open, requiring students to bundle up in their winter gear even inside. Education wasn’t focused exclusively on academic subjects. Teachers taught health measures to ensure they were informed of the preventative measures they could take after they left the preventorium. This included education on hygiene, healthy living, and nutrition, things they could adapt to their life back at home.

Sun Baths

Children at preventoriums were required to spend a lot of time in the sun, earning them the nickname “Children of the Sun.” They played in the sunlight and rested in the sun in beds set on decks, on lawns, anywehre exposed to the sunlight. During winter nights, they were placed under Alpine lamps to get artificial sunlight for ‘light therapy’. This was heliotherapy, using the sun’s natural energy to build a child’s health and vigor. Heliotherapy exposed the tuberculosis bacterium to light, something the children were deprived of in their dark urban tenement homes, and kill it off. While there wasn’t exactly scientific data to back up the claim, sanitoriums and preventoriums in North America and Europe believed the sun could heal and prevent poor health – especially tuberculosis – from becoming a larger problem.

Preventorium Schedule

Children at preventorium were kept on a tight schedule. The Fort Alexander preventorium in Manitoba, Canada gives a glimpse of life in a preventorium. Patients woke at 7:00am. After breakfast, they went to school from 8:30 am until 10:30. Outdoor play time lasted until 11:45, lunch at noon, then a one-hour rest period from 12:30pm to 1:30 pm. The rest period included a “sun bath” to expose them to the fresh air and sunshine. Patients had school for another hour. At 2:30, patients went outside until dinner. At 5:00, they ate, took a shower at 5:45, then had their temperature recorded. Bedtime was 7:00 pm, giving the students more than twelve hours of sleep. Additionally, patients choked down a tablespoon of cod liver oil twice a day. And once a day they had a dose of Iron Tonic.

Fresh Air, Sunshine and Food: Why Not Just Do This at Home?

In his contemporary observation, Kleinschmidt (1930) expressed concern that some preventoriums as “routinely operated asylums, having only a vague notion of that the real needs of the beneficiaries are and what they are actually trying to achieve.” But he felt they were a vital tool against tuberculosis. Doctors knew the preventive care the facilities offered could be done at home. After all, fresh air and sunshine were free, and nutritious food available in stores. But these requirements were not available for everyone. They were concerned about families that couldn’t – or worse, would not – provide these things. Some families had no means to buy the recommended food. Some children lived in homes where windows had to remain shut for safety or logistical reasons. Others had children working or had their time monopolized and could not get them outside when the sun was at its most beneficial.

Preventoriums Were Scary

Adults might find the idea of escaping ‘real life’ for a doctor-mandated light workload and extra rest luxurious. But these were healthy children leaving their homes. While some patients left home situations fraught with abuse and neglect, others were terrified to be on their own in the residential boarding-style preventorium. Charles Felton, in a 2023 interview with The Tribune-Democrat in Pennsylvania, USA, spent time at the Cresson preventorium in the 1950s. In his experience, “The problem is that many of these children have no understanding – and even now as adults – as to why they had to leave their families and go to Cresson.” Another Cresson patient remembers the “long, scary road” to the facility, where she would stay for six months, being subjected to medical tests, medicines to stave off TB, and isolation.

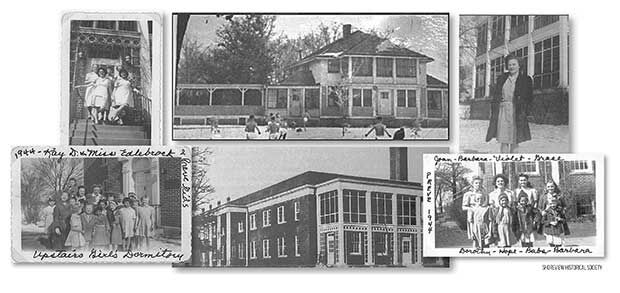

Preventorium Were Not Equal Opportunity

Preventorium reflected the racial and social attitudes of the day. Patient admissions were quite discriminatory in the United States. Data from Ramsey County, Minnesota, report seven times more African-Americans died of tuberculosis than European-Americans between 1915 and 1950, preventorium only accepted one African-American girl, nine-year-old Velma Holland, who arrived 1915. Her mother had died of tuberculosis. Her father frequently traveled for work, so the preventorium cared for her as she tried to stave off the disease. Unfortunately, she succumbed to tuberculosis while at the preventorium two years later. It wasn’t common for patients to die at preventorium, at least at the Ramsey County facility, but aside from the trauma and fears of other patients for their own health, officials made some wild speculations.

Preventorium Populations Often Lacked Diversity

The death rate for African Americans was higher than that of Caucasian tuberculosis cases a rate of seven to one. Instead of looking for racial, social and economic factors, officials at the time believed that African American people just rarely recovered from tuberculosis. Due to this pessimistic attitude, preventorium admitted an extremely small number of African American children. The preventorium in Shreveport, Louisiana admitted African-American patients at the height of the preventorium movement. It was one of the few across the United States to do so. The Ramsey County facility would not admit African Amiercan children again until 1950. Even then, the facility only admitted three children from the same family.

Hispanic population welcome at Minnesota facility

While the Ramsey County preventorium experience excluded African American children, it had a very different stanceabout the Hispanic population during its thirty-eight year run. The same preventorium that saw the death of young Vera Holland mark the end of African American participation in local preventoriums was conversely welcoming to the Hispanic population. The same region reported 54 patients with Spanish surnames admitted between 1926 and 1953, despite the hundreds of children admitted to preventoriums during that period. A high proportion of these children lived in the low-income West Side Flats; a complex known for its poor conditions. The Ramsey County Preventorium admitted patients from the Flats since its early years, when the the local Jewish immigrant population lived there. As the demand for preventoriums fell, the facilities continued to recruit from the Flats even as the demographic changed.

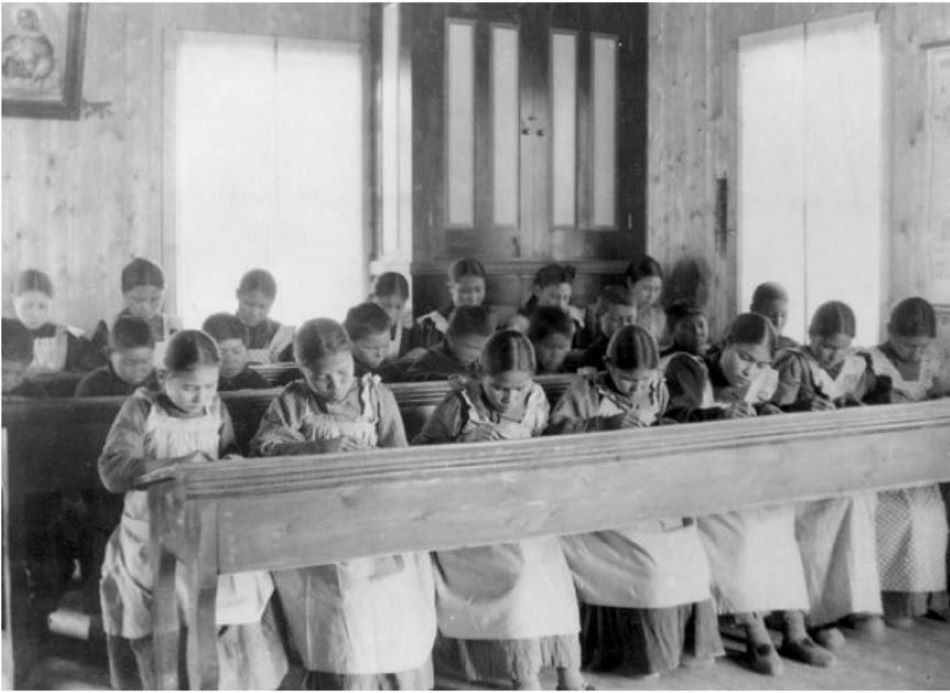

Preventorium inequity in Canadian Indigenous Communities

In Canada, tuberculosis was a problem among Indigenous people. Canadian religious groups had operated residential schools for indigenous populations in Canada since 1831. But these schools were rife with neglect and tuberculosis. The disease ravaged the student population at an alarming rate. Schools didn’t have the money or technology to combat the diseases affecting their students, so in the 1930s, Canada’s government intervened. They put tubercular students in sanitariums to isolate Indigenous populations with tuberculosis, filling beds vacated by non-Indigenous people who went home for outpatient treatment. Public health officials and the Canadian government believed indigenous patients wouldn’t follow up on treatment. They worried the Indigenous communities lacked the facilities and medical staff necessary to complete treatment. Because of this, Indigenous patients had to stay at sanitorium when non-indigenous people did not. This idea carried through to the preventorium populated by Indigenous children.

Funding cancels the Fort Alexander preventorium

But the indigenous preventorium at Fort Alexander treatment seemed successful. By December 1938, doctors reported all of the students were healing. The tuberculosis lesions were going away and none of them had to move to a sanitorium. Despite the improving health seen in the preventorium children, doctors recommended discontinuing the preventorium in 1939. Some doctors feared sending patients back into the general student population could expose healthy children to tuberculosis. But there was nothing they could do. The school could not afford to continue operating the program and build a separate dormitory, school, and play area to keep healthy and pre-tubercular populations apart. The preventorium children had to go either to the sanitorium, to the ‘regular’ school, or to their home. Five select children stayed and completed the protocol as Indigenous Canadian preventorium slowly phased out of existence.

Preventorium Criticism

Despite preventoriums opening up all over North America and Europe, they had their share of critics. In 1933, the National Tuberculosis Association called preventorium “…neither necessary nor desirable.” The founder of Lymanhurst, Dr. Arthur Lyman, kept meticulous records about its patients and their medical condition. After years of tracking the data, Lymanhurst officials reviewed the outcomes and found that preventorium treatment was no more efficient for preventing the escalation of tuberculosis than simply waiting it out at home. The Lymanhurst preventorium closed in 1934. Dr. Lyman, reflecting on the experience, called preventorium “fresh air faddism.” Physician Chester Stewart said preventorium were “scientifically impractical,” despite the good sentiment behind them. Yet preventorium would remain open for roughly another twenty years.

1950s: Preventorium Shut Down

In 1921, Albert Calmette and Jean-Marie Camille Guerin created a vaccine to combat tuberculosis, but more work is necessary in tuberculosis vaccine research. Modern treatments center around antibiotics. Antibiotics are a vast improvement over historic “cures” of vinegar massage, inhaling hemlock, or the “royal touch” (literally having a king or queen, living gods on earth, touch the sick person). But the vaccine wasn’t perfectly effective; 8390 sanitoriums able to treat 136,000 people were still in operation in 1953. Despite the 1.6 million deaths worldwide attributed to tuberculosis each year to this day, sanitorium are no longer a popular way to treat the disease and manage its spread. Today it’s a drug regimen and rest. Preventorium shut down in the 1950s after vaccination became more common, although it has not stopped the disease. But treatment today doesn’t require isolating in a remote facility like preventorium or sanitorium.

Preventorium is Just a Vague Memory

Today “healthy” latent tuberculosis patientsrecieve medicine to eliminate tuberculosis bacteria in their system before it becomes the full-blown disease. The era of preventorium was over. Hindsight raises questions about taking children from their homes for months or years to give them play time, sun, nutritious food, and rest, but as Janine Chamber of the National Lung Association said, “People were so afraid of TB, so I could easily imagine they thought they were protecting their children.” Preventoriums were an experimental facility to try to stop a deadly disease. For some Children of the Sun, it was isolating and lonely. But for others, coming from situations where they were abused or neglected, it was a home. Despite doctors’ efforts, preventorium wasn’t the solution to tuberculosis they hoped it would be and left more than one child with terrible memories.

Where did we find this stuff? Here Are Our Sources:

Preventorium at residential schools. Kaila Johnston, Defining Moments Canada: Bryce100, Accessed 23 October 2023.

Remembering the ‘Children of the Sun.’ Kathy Mellott, The Tribune-Democrat, 6 September 2009.

Reventoria. C.M.H. Diseases of the Chest, 4(2), February 1938, p. 6.

The children’s preventorium of Ramsey County. Paul Nelson, MnOpedia, 14 August 2023.