Medical theories and beliefs can undergo radical changes over time. Take beards. A few centuries ago, beards were out of fashion, and facial hair was seen as bodily waste, a repugnant substance best gotten rid of. Then facial hair made a major comeback in the Victorian era, driven in part by a medical belief that beards could prevent illness. Below are twenty five things about that and other odd medical history facts.

Medical Opinions Once Saw Beards as Bodily Waste

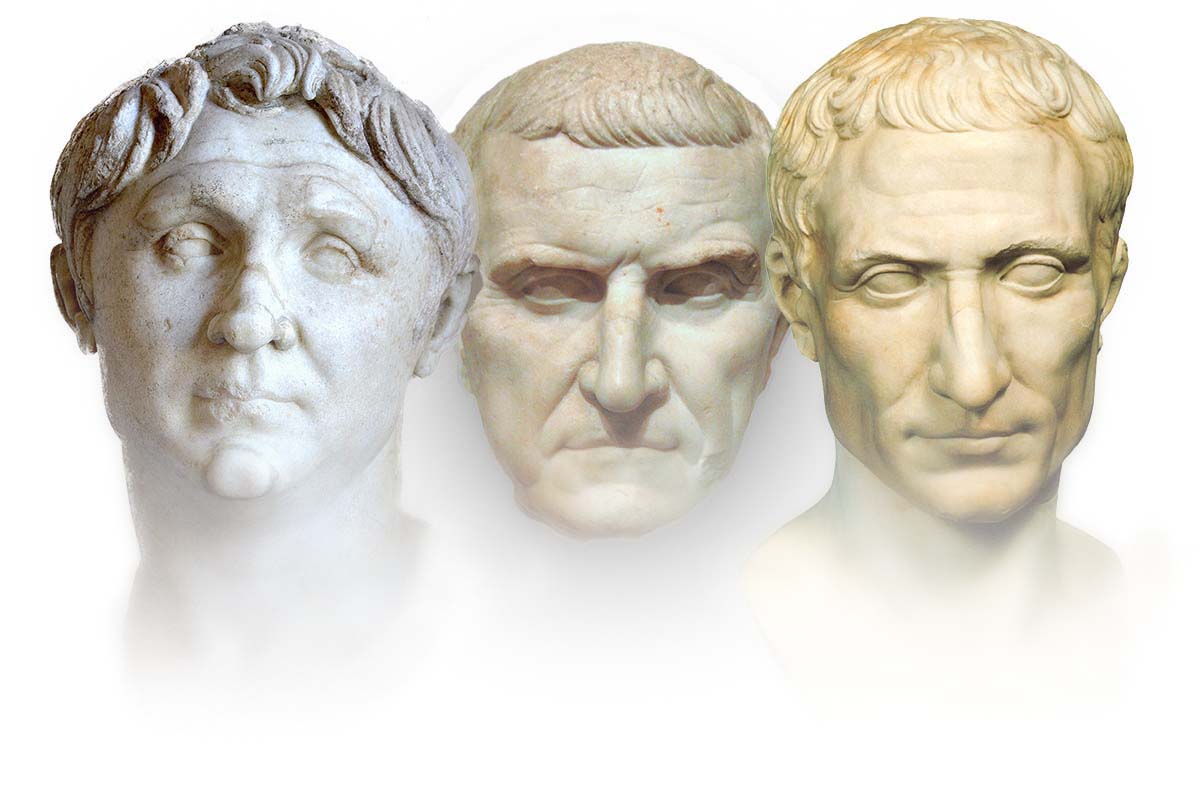

Beards, once considered outdated in the Western world, experienced a resurgence in popularity, largely attributed to the influence of hipster culture. However, this cyclical pattern is not new, as beards have faced shifts in fashion throughout history. In ancient Greece, for example, beards were initially in vogue but fell out of favor during the Hellenistic era. A similar trend occurred in the early Roman Republic, where leaders sported beards, only for the clean-shaven look to dominate for centuries until Emperor Hadrian reintroduced facial hair as a fashionable choice. The medieval era witnessed fluctuating beard trends, but by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, medical beliefs deemed facial hair a form of bodily waste, leading to a prevailing preference for shaved faces among Enlightenment-era men.

The nineteenth century witnessed a dramatic reversal in facial hair trends, driven by the Victorian ideal of rugged manliness. The resurgence of beards aligned with changing cultural norms and medical opinions touting health benefits. Victorian doctors, influenced by concerns about air pollution from the Industrial Revolution and emerging germ theory, theorized that thick beards could filter out harmful particles and prevent illnesses. Despite later revelations that beards cannot effectively filter air and may even increase infection risks by trapping germs, the nineteenth-century fascination with facial hair reveals how evolving cultural ideals and incomplete medical understanding often shape grooming trends.