The human body is an amazing thing. For each one of us, it’s the most intimate object we know. Yet most of us don’t know enough about it. While you may only think of your stomach when you’re eating or it catches your attention with a gurgle or burble, it’s much more than a repository for the food you eat. Your stomach kills microbes, secretes hormones and mucus, and absorbs nutrients. Your stomach has 3 main functions: The temporary storage for food, which passes from the esophagus to the stomach where it is held for 2 hours or longer. Mixing and breakdown of food by contraction and relaxation of the muscle layers in the stomach and The digestion of food.

While food is only in the stomach for two to five or six hours before it’s sufficiently broken down to pass along the line to the intestines. The abdomen contains all the digestive organs, including the stomach, small and large intestines, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder. These organs are held together loosely by connecting tissues that allow them to expand and to slide against each other. Below you will find everything you need to know about your vital digestive organs.

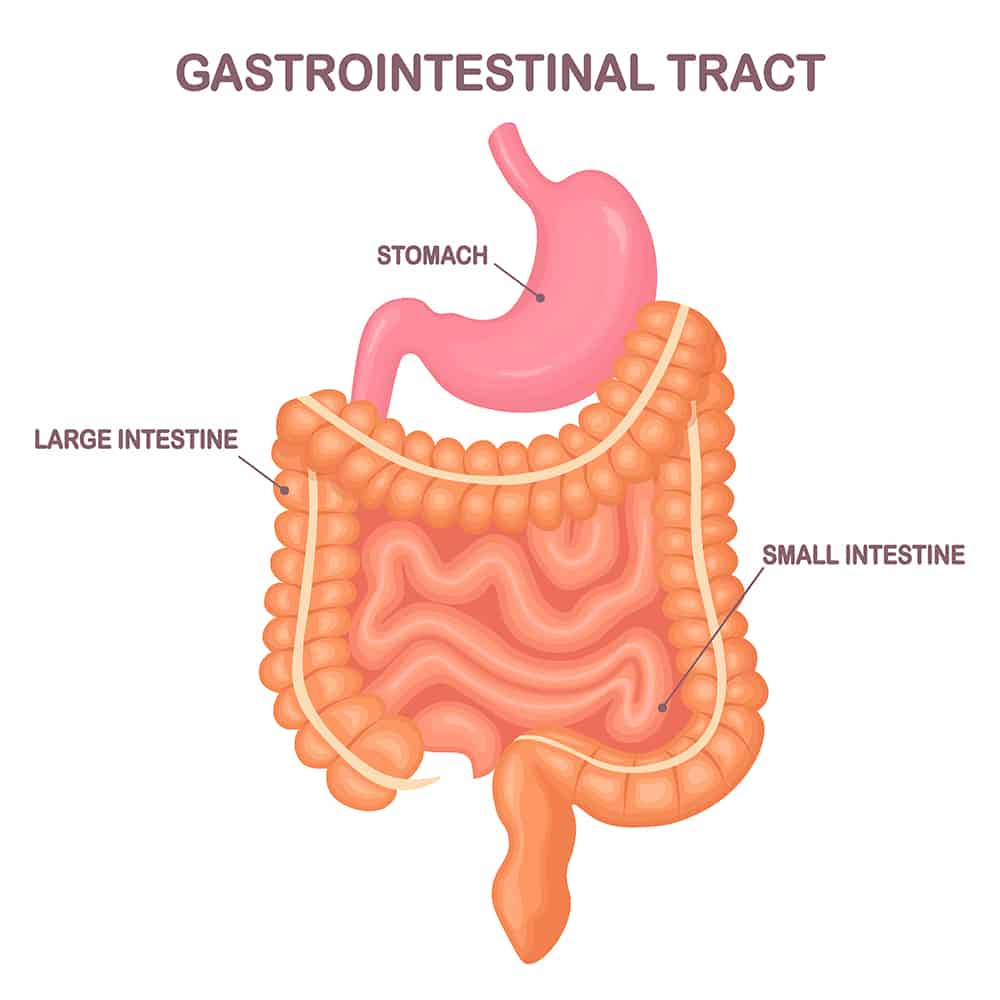

1. What exactly is the Gut?

The gut (gastrointestinal tract) is the long tube that starts at the mouth and ends at the back passage (anus). The mouth is the first part of the gut (gastrointestinal tract). When we eat, food passes down the gullet (esophagus), into the stomach, and then into the small intestine. The small intestine has three sections – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine and follows on from the stomach. The duodenum curls around the pancreas creating a c-shaped tube. The jejunum and ileum make up the rest of the small intestine and are found coiled in the center of the tummy (abdomen). The small intestine is the place where food is digested and absorbed into the bloodstream.

Following on from the ileum is the first part of the large intestine, called the caecum. Attached to the caecum is the appendix. The large intestine continues upwards from here and is known as the ascending colon. The next part of the gut is called the transverse colon because it crosses the body. It then becomes the descending colon as it heads downwards. The sigmoid colon is the s-shaped final part of the colon which leads on to the rectum. Stools (feces) are stored in the rectum and pushed out through the back passage (anus) when you go to the toilet. The anus is a muscular opening that is usually closed unless you are passing stool. The large intestine absorbs water and contains food that has not been digested, such as fiber.