In the medieval era, people treated medical advice like they were collecting trading cards of magical missteps. Forget evidence-based medicine; it was more like “Let’s play a game of ‘Guess What Ails You’ with a side of ‘Is That Unicorn Horn or Just a Really Fancy Goat Antler?'” Bloodletting was all the rage, as if the cure for everything lay in the depths of your veins, and if you had one too many humors, well, that’s what trepanation was for – just drill a hole in your head, and the evil spirits would be on their way out faster than a horse-drawn carriage on a medieval freeway.

And don’t get them started on miasma theory; they believed bad smells could literally kill you. In the medieval medical playbook, if you weren’t swallowing gemstones, wearing live animals as fashion accessories, or dancing under a full moon with a chicken leg, you weren’t really trying to heal. It’s a good thing modern medicine decided to skip the alchemy and embrace, you know, science.

Bloodletting

Bloodletting in the Middle Ages was the medieval equivalent of trying to fix a computer by smashing it with a hammer – an attempt to solve health issues with questionable methods. Based on the ancient concept of balancing bodily humors, practitioners believed that draining a patient’s blood could restore equilibrium and treat various illnesses. Picture this: you walk into a dimly lit chamber, and a self-proclaimed expert brandishing a collection of sharp instruments greets you.

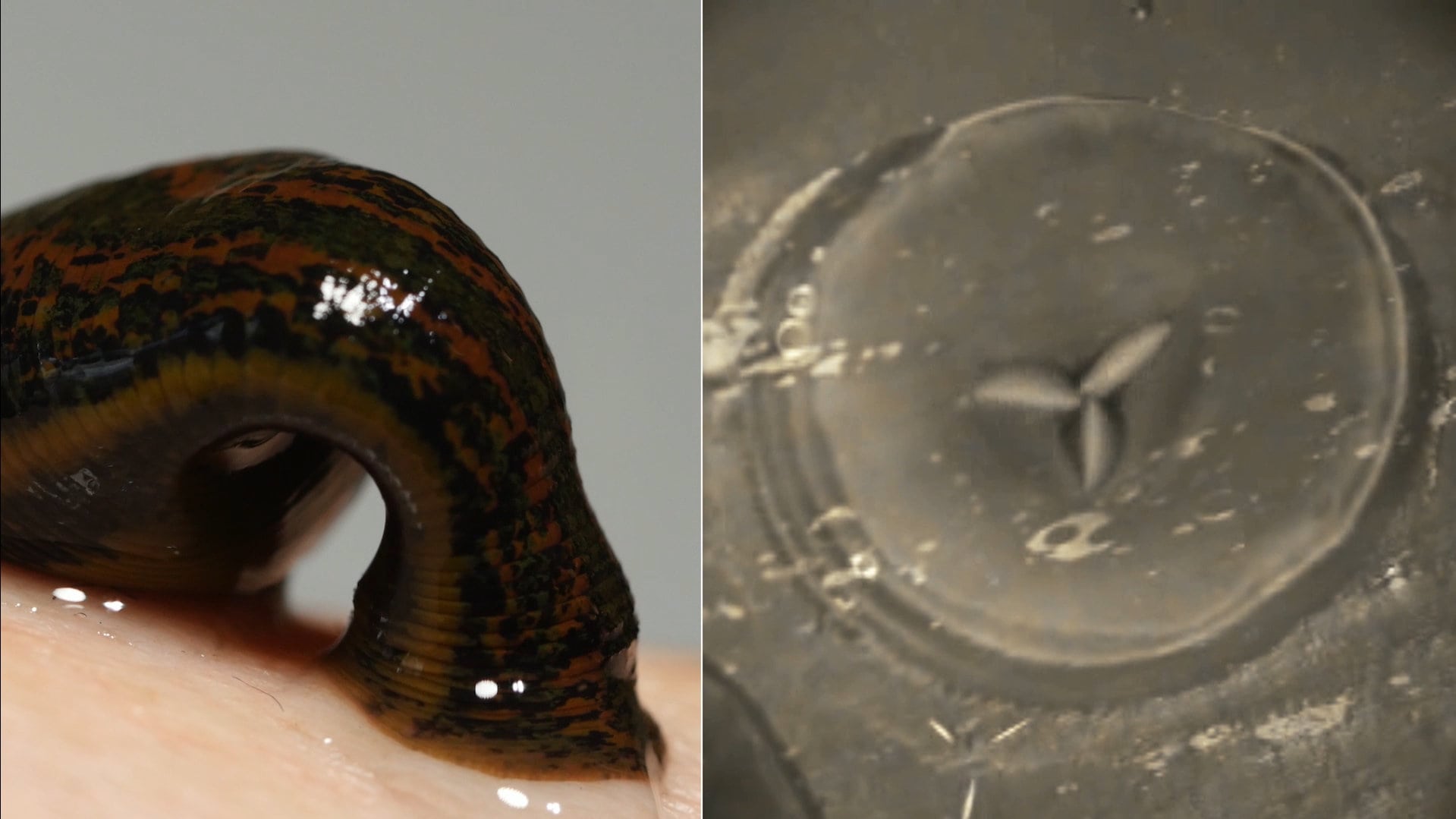

Need a cure for a headache? Let’s drain some blood. Feeling a bit feverish? How about a pint or two? The bleeding process involved leeches, lancets, or even cupping, leaving patients looking like they lost a battle with a particularly enthusiastic vampire. Despite its widespread use, bloodletting often did more harm than good, contributing to the weakening of already ailing patients. It wasn’t until the dawn of modern medicine that people realized letting blood spill like it was going out of style might not be the best prescription for wellness.